The boreal forests, the largest terrestrial biome on the planet, are vast coniferous forests spanning across the northern hemisphere. You can find the boreal forests from eastern Canada all the way through Russia and Northern Europe.

The land of the mosses, that’s what we call our boreal forests here. Why? Because moss covers up to 97% of Canada’s boreal forest surface.

As much as 20% of our forest biomass comes from moss & lichens, which is massive for an organism we know so little about.

Moss & lichens also play a significant role in the ecosystem, they are an important source of food for boreal forest mammals & insects. Additionally, they colonize rock surfaces, slowly break them down, and add new minerals to the soil.

Their life and death cycle also add much organic matter to the forest floor. In truth, decomposed mosses and lichens create significant sources of new topsoil.

Black spruce saplings, for example, really like to grow in fresh or decomposing moss.

Did you know? Mosses & Lichens are old… I mean really old!

Did you know the earliest “moss” species began appearing in the Ordovician Period? That’s as far back as 443 million years ago!

They are some of earth’s very first terrestrial plant life!

And later in earth’s history, during the Permian Period, land masses all fused into a supercontinent called Pangea. That’s why many moss & lichen species that evolved back then are found all over the world today, even as far as Australia.

Did I pique your interest? This sure got me…!

So here’s what you can expect to read in this article:

We will cover these topics on boreal forest moss & lichens:

- How to Differentiate between Moss & Lichens

- Common Boreal Forest Mosses & Lichens

- How to Identify and Recognize each Species

- Do they have any Significant Use? i.e., Medicinal or Commercial value

Alright, let’s delve into the fascinating world of mosses & lichens!

What’s the Difference Between a Moss and a Lichen?

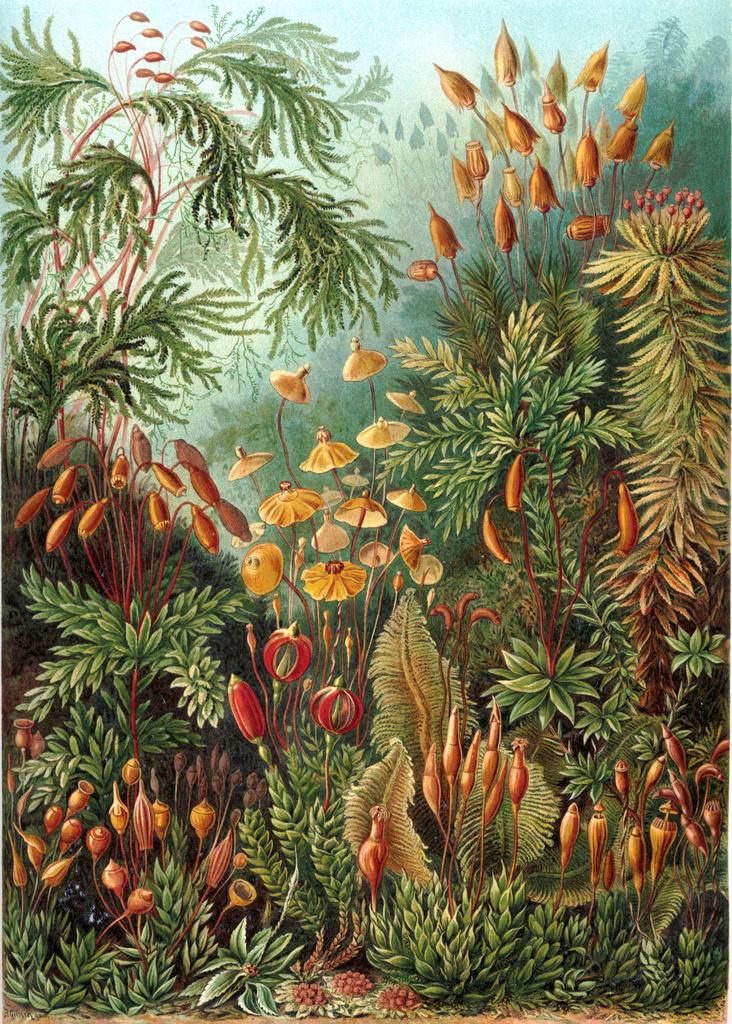

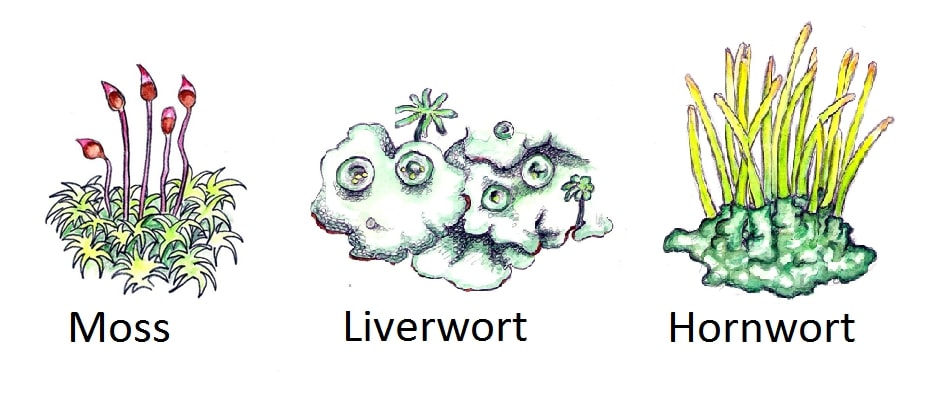

First, the word moss is often used in a general way but mosses are actually sub-families of a type of organism called a bryophyte.

Bryophytes, in short, are non-vascular seedless plants.

Non-vascular organisms like bryophytes are often classified into three divisions:

- The Mosses (division Bryophyta)

- The Liverworts (division Marchantiophyta)

- The Hornworts (division Anthocerotophyta)

Lichens, on the other hand, are a completely different thing. They’re actually not even plants! Lichens are in fact, a symbiosis between two organisms: a fungus and algae.

What we see when we look at lichen is the fruiting body of the fungus, but down to the microscopic level, the fungus is colonized by cyanobacteria.

The relationship is mutually beneficial. The cyanobacteria produce organic carbon compounds through photosynthesis, and in return, the fungi give the algae/bacteria a body to live on outside of water.

There’s a variety of species in each division, let’s take a look:

The Most Common Boreal Forest Mosses

The Mosses (d. Bryophyta)

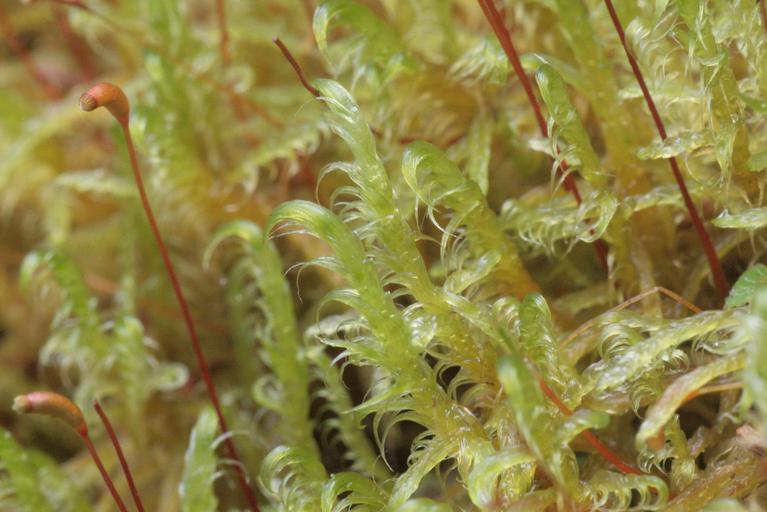

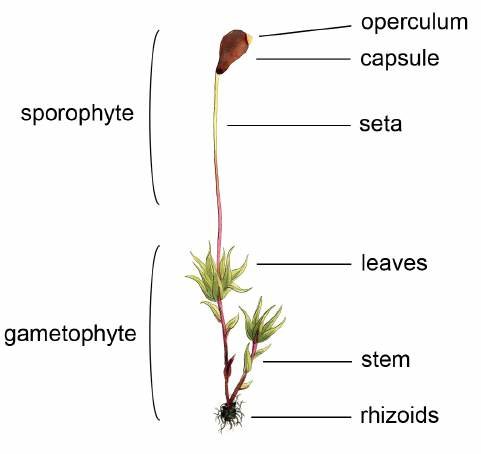

Mosses have two important visual characteristics you can look at to differentiate each species:

- The gametophyte: Observe the lengths of their stems, leave shapes, and patterns.

- The sporophytes: Observe their spore-distributing stalks, and the shape of their capsules.

These two characteristics of mosses vary from species to species. Some species look ridiculously similar, but if you carefully look at these two features, you will be able to differentiate them.

How does moss reproduce?

Moss are some of the oldest organisms on the planet, their reproductive system is efficient. They can reproduce sexually and asexually.

- The sporophytes are the reproductive organ of moss. They create spores that get picked up by insects or the wind. This is the main technique mosses use to spread their colonies to locations distances away.

- Mosses can also reproduce asexually by brood bodies or fragmentation. This is the main technique mosses uses to multiply the immediate spread of ‘mother’ colonies.

- Brood bodies: They grow on existing stems, fall down by their weight and create rhizoids to attach themselves to a soil, rock or debris.

- Fragmentation: When a piece of moss seperates from the mother colony, it has the capability of regenerating on its own. It then grows into a new clone of the mother colony.

Now let’s look at some of the most common boreal forest mosses of the bryophyta phylum:

Ribbed Bog Moss (Aulacomnium palustre)

Stems & Leaves: Yellow-green, each stem grows from 3-9cm tall. Leaves are lance-shaped, with a sharp point, 3-5mm long.

Sporophytes: Red-brown, up to 4cm tall. The capsules are slightly inclined and curved, they have strong, visible groves.

Golden Ragged Moss (Brachythecium salebrosum)

Stems & Leaves: Loosely erect or erect-spreading, sometimes curved and pointed in 1 direction. Leaves are no more than 3mm long.

Sporophytes: They produce single, yellow-red stalks ranging from 1-3cm long. Blackish capsules 1-3mm long, oblong-cylindrical shaped.

Broom Mosses (Dicranum polysetum/scoparium )

Dicranum polysetum

Dicranum scoparium

Stems & Leaves: Light to yellow-green color, spread over large areas of ground with rhizoids. Leaves up to 1cm long, spreads near perpendicular to stem.

Broom mosses are one of the iconic boreal forest moss & lichens.

Sporophytes: Can have from 1-5 stalks for each plant, 2-4cm long. Inclined, and curved.

Sickleleaf Hook Moss (Sanionia uncinata)

Stems & Leaves: Long, narrow, pleated lengthwise. Leaves are all turned to the same side in a crescent shape.

Sporophytes: Long red stalks (1.5-3cm). Twisted from side to side, capsules (2-3mm) have a strong curve almost horizontal.

Stepped-hair Moss (Hylocomium spendens)

Stems & Leaves: Smooth, oval-shaped leaves (2-3mm) with abrupt tips.

Sporophytes: Uncommon to spawn, red stalks (1-3cm). Brown, inclined capsules with a long beak on the lids.

Big Red Stem Moss (Pleurozium schreberi)

Stems & Leaves: Leaves are oblong to oval, rounded at tips, inrolled at sides. Stems orange to reddish, irregularly pinnately branched, ascending, 5 – 12 cm tall; forms light green to yellow-green mats.

Sporophytes: Uncommon; stalks red to yellowish, 2 – 4 cm tall; capsules cylindrical, 2 – 3 mm long, horizontal.

Juniper Hair Cap (Polytrichum juniperinum)

Stems & Leaves: Bluish-green, shiny, short to long, slender to stout, upright, unbranched; grows in mats or more rarely as closely associated individuals; stems 1-10 cm tall. Leaves are 4-8 mm long, upright-spreading when dry, wide-spreading when moist.

Juniper hair Caps are one of the iconic boreal forest moss & lichens.

Sporophytes: Common; stalk upright, wiry, 2-6 cm long, reddish; capsule white-brown, 2.5-5 mm long, 4-sided, vertical, becomes horizontal with age.

Common Hair Cap (Polytrichum commune)

Stems & Leaves: Dark green, robust, unbranched, 4-15 cm tall or more; single-sexed, males have enlarged heads at plant tips, females produce sporophytes; lower portion covered by grey rhizoids. Leaves are 6-10 mm long, lance-shaped, sharply pointed;

Sporophytes: Common, at plant tips; stalk wiry, very long; capsules horizontal, 4- sided. Capsule hood has tuft of hair at tip, covers entire capsule.

Knight’s Plume (Ptilium crista-castrensis)

Stems & Leaves: Green to golden-green, 3 – 12 cm long; branches somewhat upright to drooping, symmetrical, feather, tapered. Branch leaves pleated, egg-shaped, to 2 mm long, all curled towards branch below

Sporophytes: Stalk reddish, 2 – 4.5 cm long; capsule chestnut brown (green when sprouting), nearly horizontal, 2 – 3 mm long, curved.

Shaggy Moss (Rhytidiadelphus triquetrus)

Stems & Leaves: Wide-spreading masses; dark- to bright-green or yellowish-green; up to 10 cm tall. Stem leaves egg- to heart-shaped, with a long tapered and pointed tip.

Sporophytes: Cylindrical, curved capsules, horizontal to hanging; stalks reddish-brown.

Rusty Brown Sphagnum (Sphagnum fuscum)

Stems & Leaves: Brown to greenish-brown; stems slender, brown, individually less robust than other peat mosses, in very compact hummocks.

Sporophytes: Stalk short (1-2 mm); capsule chocolate brown, 1 – 1.5 mm long.

Small Red Peat Moss (Sphagnum capillifolium)

Stems & Leaves: Small, reddish, with rounded, convex head. Leaves are broadly egg-shaped.

Sporophytes: Stalk short (1-2 mm); capsule chocolate brown, 1 – 1.5 mm long.

White-Toothed Peat Moss (Sphagnum girgensohnii)

Stems & Leaves: Medium-sized, green, robust, forms loose mats; head (capitulum) is star-shaped. Stem leaves broadly tongue-shaped, torn along edge across flat top

Sporophytes: Sporophytes are uncommon.

Midway Peat Moss (Sphagnum magellanicum)

Stems & Leaves: Medium-sized to large, reddish to reddish-purple, sometimes light green when growing in shade; branches in clusters of 4 – 6, with 2 – 3 spreading away from the rest.

Sporophytes: Single; stalk short; capsule dark brown, spherical, erect, smooth.

Tree climacium (climacium dendroides)

The Liverworts

Liverworts are flowerless plants that produce spores in small capsules. They often appear in these two forms:

- Leafy: Liverwort gametophytes appears as stems with leaves, they can easily be confused with mosses.

- Thallose: Liverworts appear as a flattish, green sheet – possibly wrinkled or lobed.

Just like mosses, liverworts have rhizoids. These are anchoring structures, superficially root-like, but without the absorptive functions of true roots.

Cells of about 90% of liverwort species contain oil bodies. The compounds found in these oil bodies are various terpenoids and the amount produced varies between species. They are useful for identification.

In many cases the functions of these compounds are unknown, but they do give distinctive aromas or tastes to various liverworts.

Liverwort sporophytes can appear as regular stalks with a capsule at the end or in other unique ways. For example, some sporophyte of genus marchandia appears as umbrella-like structures, where the spore capsules are formed on the undersides.

Liverworts found in the boreal forest:

Greasewort (Aneura pinguis)

Anomalous Flapwort (Mylia anomala)

Green-tongue Liverwort (Marchantia polymorpha)

Narrow Mushroom-headed Liverwort (Marchantia quadrata)

Juratzka’s Silverwort (Anthelia juratzkana)

Pale Liverwort (Chiloscyphus pallescens)

Cat-tonque liverwort (Conocephalum salebrosum)

Common Fold-leaf Liverwort (Diplophyllum albicans)

Northern Naugehyde Liverwort (Ptilidium ciliare)

Comb Liverwort (Riccardia multifida)

Jameson’s Liverwort (Syzygiella autumnalis)

Naugehyde (Ptilidium pulcherrimum)

The Hornworts

Hornworts are flowerless, spore-producing plants that typically produce their spores with long horn-like antennas. These develop from gametophytes that are often flattish green sheets just like liverworts.

The male and female gametes (sperm & egg) are produced on the thallus (those green sheets). These fertilized eggs will develop into the sporophyte (the tapering, long, horn-like structure).

Hornworts don’t have the slime papillae that are found in many liverworts, yet have the ability to create mucilage in almost any cell.

Since bryophytes don’t have the traditional root systems of other plants, the mucilage (slime) acts as a way to store water and food from the surrounding environment. The mucilage also plays a big role in creating the right environment for sperm and egg fertilization within the archegonium.

All hornworts have Nostoc cavities. A special mucilage cavity where a microorganism called nostoc can enter. Once inside, this microorganism multiplies and provides the hornworts with nitrogen, in exchange for carbohydrates, forming a symbiosis.

Hornworts found in the boreal forest:

Macoun’s Anthoceros (Anthoceros macounii)

Carolina Phaeoceros (Phaeoceros carolinianus)

Field Hornwort (Anthoceros agrestis)

Smooth hornwort (Phaeoceros laevis)

The Lichens

Lichens are a combination of two organisms, a fungus, and algae. The fungus is the dominant partner, the one we visually see, and the algae are microscopic.

The algae are often green or blue algae, a type of cyanobacteria. These two types of bacteria are often present at once on lichens.

This relationship between the two organisms is symbiotic: Fungus cannot naturally photosynthesize, they lack the green pigment chlorophyll, but algae can.

So in this way, we can see it like the fungus is doing a sort of ‘agriculture’ with the algae. It provides the algae with a body and protection outside of water, which benefits the algae and in exchange the fungus receives nourishment.

Interestingly, this interesting relationship allows both species to live in environments they wouldn’t normally live in. For example a hot desert, a cold boreal forest, or even a completely exposed surface.

Lichen Appearance

When dry, a lichen will take the color of the original fungus, it can be light or dark grey color. But that’s a whole different thing when they’re wet.

When lichens are wet, their true colors shine. This is because the fungal cells in the upper cortex become transparent and the colors of the algal or cyanobacterial layers can shine through.

The colors of the blue and green algae will become much more apparent. True lichen colors can range from white to blue, green, brown, orange, and shades of grey.

Lichens found in the boreal forest:

Star-tipped Cup Lichen (Cladonia Stellaris)

Description: The lichen is pale-yellowish green (wet) or grayish-yellow (dry), forming characteristic compact large rounded or semi-rounded (cauliflower-like) heads, singly or in mats, lacking a main stem, but with many intricate branches, having wide open axils. The branch tips are formed in star-like clusters surrounding a large opening, showing very little combing.

Star-tipped cup lichen are some of the iconic boreal forest moss & lichens.

Reproduction: Small dark fruiting bodies occur at the tips of the branchlets. Small globular bodies containing a red jelly (in fresh material visible microscopically) also occur at the tips of branchlets.

Pixie Cup (Cladonia asahinae)

Freckle Pelt Lichen (Peltigera aphthosa)

Yellow Reindeer Lichen (Cladina arbuscula ssp. mitis)

True Reindeer Lichen (Cladina rangiferina)

British Soldiers (Cladonia crystatella)

Boreal Oakmoss Lichen (Evernia mesomorpha)

Lustrous Camouflage Lichen (Melanohalea exasperatula)

Dog Lichen (Peltigera canina)

Star rosette lichen (Physcia stellaris)

Punctured Ramalina (Ramalina dilacerata)

Bristly Beard Lichen (Usnea hirta)

Photo by Jersy Opiola / CC BY-SA 4.0

Photo by Avereanu / CC BY-SA 3.0

Poplar Sunburst Lichen (Xanthomendoza hasseana)

Powdered Sunshine Lichen (Vulpicida pinastri)

Photo by Friedemann Leh / CC BY-SA 3.0

Photo by Rainer Burkard / CC BY-SA 3.0

Significant Uses of Boreal Forest Moss & Lichens

Medicinal Use

There are records of mosses used as medicine dating back to ancient times. Although marginal considering how hard they are to identify. Their size is small and they often lack fruiting bodies or significant organs to attract attention.

Additionally, many mosses have no smell or flavor, with the exception of some liverworts that contain aromatic oils.

For a long time, mosses, in general, were overlooked as medicinal plants, but they have been given a chance again in the last 200 years.

Bryophyte interest was sparked up again in the late 1800s, studies were made on a variety of species. Interestingly, at least 16 species were confirmed to have medicinal properties.

Here are the confirmed medicinal properties of some of these mosses. I’ve also linked the image on this article of each relative plant listed below.

This is in no way medicinal advice, it’s a representation of researches done on these mosses. Please consult a doctor before trying any of the plants below.

- Brachythecium species: Dressing Wounds.

- Diplophyllum albicans: Antimicrobial, antifungal and antiviral.

- Marchantia polymorpha: Cytotoxic, antimicrobial, antifungal and, antiviral, inhibitory activity against 5-lipoxygenase, calmodulin, hyaluronidase, cyclooxygenase, DNA, polymerase b and a-glucosidase, cathepsin L and cathepsin B inhibitory activity. Antifungal activity.

- Polytrichum commune: Cytotoxic, anti-cancer, and proapoptotic. Antibacterial and Anti-neuroinflammatory.

- Polytrichum juniperinum: Antibacterial action against Bacillus cereus, Enterococcus faecalis, Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes. Cytotoxic and antiproliferative against the following lines of neoplastic cells: rat glioma, human epidermoid carcinoma, human lung cancer, human breast cancer, human intestinal cancer and mouse Sarcoma 37 cells.

- Ptilium crista-castrensis: Antibacterial against Proteus mirabilis, Bacillus cereus, Escherichia coli; antiproliferative against lines of neoplastic cells: rat glioma, human epidermoid carcinoma, human lung cancer, Mus musculus skin melanoma, human breast cancer and human intestinal cancer.

- Sphagnum species: Odor absorbent for personal hygienic uses, and a historical but powerful wound dressing material. A polysaccharide compound called sphagnan induces Maillard reaction with proteins, lowers the pH and binds nitrogen compounds (including amino-acids and enzymes). Food preservation.

Additional Uses

Moss & lichens have other uses in sectors like gardening, and home decor.

It could be profitable to grow them artificially to sell to gardening centers. They make great cover crops in gardens, benefit other plants, and beautify your garden.

Moss terrariums make wonderful indoor desk pieces.

Additionally, as rooftop gardening grows in interest, the demand for mosses is likely to rise. A variety of mosses and lichens can grow in open areas like rooftops and easily greenify our cities.

We could only draw advantage from knowledgeable urban designers sharing their thoughts on moss use in city landscaping.

Conservation

It’s been wonderful to see many databases online documenting the hundreds of varieties of these wonderful ancient plants. My home province of Quebec is home to such conservation programs, they bring awareness to the curious like me and list all biodiversity hotspots.

Evidently, to save these species, and many others, we must continue to create and protect nature reserves. It’s certainly a thing that’s easier said than done, but public awareness can certainly help in the execution of these programs.

Each species have an intrinsic value which cannot be disputed, even the smaller plant species like mosses and & lichens do.

Hopefully, the wonderful world of boreal forest moss & lichens inspired you as much as it inspired me! May we all do our part to preserve earth’s wonderful biodiversity.

Cheers.

Sources:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0254629919301693

https://www.borealforest.org/lichens.htm

https://explorer.natureserve.org/